When I was 12 years old, my family took our first trip outside the United States.

We came to Israel on a two-week family tour. It was July 1982. The Lebanon War had just begun. In retrospect, it was the first step on what has become my lifelong Zionist journey.

I was moved by everything I saw. The IDF soldiers hitchhiking home for leave from the battlefields in Lebanon looked like movie stars. Ma’aleh Adumim, now a major city, was a clutch of mobile homes in the desert but the gleam in the eyes of the settlers showed the promise of what was to come.

The markets of Jerusalem, the beaches in Tel Aviv, the shells of Syrian tanks on the Golan Heights and the fish in the Sea of Galilee captivated my imagination.

The Western Wall awoke me to the immutable fact that the Nation of Israel, the Land of Israel and the Law of Israel are indivisible.

Hearing Hebrew, the language of prayer shouted out from every corner filled me with awe. And seeing the multiethnic society of Jews from every corner of the world shook me to my core. After two thousand years, in an act of will with no parallel in human history, Jews of all races, backgrounds, and cultures; Jews with unique, fervently kept traditions came home and began patching together a people forcibly separated for 50 generations.

During that first trip to Israel, I understood that the future of the Jewish people was being forged in Israel, not in the Diaspora, not even in my warm community on the south side of Chicago.

I loved America. But I wanted to move to Israel.

Nine years later, in 1991, two weeks after I finished college, I fulfilled my wish. I boarded an El Al flight to Tel Aviv with a one-way ticket in my hand. A week later, I took my first step towards the second stop on my Zionist journey: the Israel Defense Force. Two months after dropping down, I started basic training.

I served in the IDF for five and a half years, leaving as a captain. Most of my service was spent in negotiations sessions with the PLO. As the coordinator of negotiations on civil affairs with the Palestinians in the Defense Ministry, I was a core – if junior – member of the Israeli negotiating team during the Oslo peace process years.

In the IDF, as in all the stations I passed in my professional life, I viewed my work as a calling. I always believed that I had the ability to impact the country and the people for the better, and that it was my duty to try to do so.

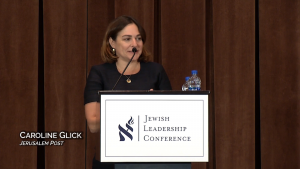

For the past 18 years, as a writer in Israeli and international media, it has been my conviction that my job is to use my pen, my keyboard and my voice to shape and expand Israel’s maneuver room whether in relation to the international arena, to military questions, to legal affairs or to political issues.

The job of a commentator is to interpret reality. The media’s habit of simplifying issues by treating everything as an either-or proposition is disastrous for formulating policy. Israel’s options are rarely binary. On almost all issues, Israel has a full spectrum of options. Yet, due to media pressure, our leaders often miss them.

To advance its interests in the international arena, for instance, Israel doesn’t need to bow before foreign powers. It needs to show foreign powers that they want what Israel has to offer and that it is in their interest to work with Israel. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is the only prime minister Israel has had that fully understands and implements this basic truth.

The same is the case with the Palestinians. Israel has nothing to fear in its dealing with the Palestinians. The choice we were presented with for more than a generation – either peace with a Palestinian state or war without one – was a false and destructive conceit. It was based on a wide array of lies and delusions. I devoted hundreds of columns and my book, The Israeli Solution, to expose them.

So too, if we want to understand historic processes unfolding, we need to understand history. I saw it as my job as a columnist to explain the relevance of history to our current challenges and to expose the ignorance of much of what passes for historical wisdom in the popular discourse, whether in relation to German history, to Jewish history, to American history, or to Islamic history.

Over the past several years, I found myself returning over and over again to the study of basic issues of governance. This was no esoteric exploit.

Over the past several years, the term “rule of law” in Israel has been turned on its head. Rather than denote the dispassionate enforcement of duly promulgated laws, it has come to mean what President Reuven Rivlin once referred to as the tyranny of the “rule of law mafia,” that is, the rule of unchecked lawyers.

Israel’s Basic Law: Knesset defines the Knesset as the sovereign. That is because the public elects its members in national elections. Members of Knesset in turn, elect the government as the executive arm of the people’s will. That is how it works in democracies. The parliament legislates laws. The executive implements policies in accordance with the law and the mandate it receives from the public at the ballot box. The job of the judicial branch is to interpret laws.

Over the past several years, and with growing intensity in the past four years, the authority of the Knesset to promulgate laws has diminished. The combined forces of the attorney-general and the justices of the Supreme Court have seized not only the power to abrogate laws and interfere with the legislative process, but to dictate laws through legal opinions and judgments. The same goes for executive power. Not only have the justices and attorneys arrogated to themselves the power to cancel government decisions and policies, they have also asserted the power to dictate policies to the government.

Through these acts of the legal fraternity, the powers of Israel’s elected officials have been whittled down. This week we learned that Supreme Court president Esther Hayut has quietly empaneled a forum of 11 justices to determine the legality of Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People.

In Israel, Basic Laws are essentially the constitutional foundations of the state.

If Hayut goes through with adjudicating petitions against the law, even if the justices rule that the Basic Law is legal, by claiming the power to adjudicate a Basic Law, the justices will seize the power to undermine the foundations of the state.

The Law of Return, which is the anchor of Jewish peoplehood and the ingathering of exiles, has long been a red flag for post-Zionist radicals who reject Israel’s right to exist as a specifically Jewish state. There is every reason to believe that if the justices seize the power to undermine Basic Laws, they will not hesitate to go after the Law of Return.

Watching this dangerous trend of events, I have used my position as a columnist to warn the public about what is happening and to empower Israel’s politicians to fight for their powers. If Israel is to maintain its democracy, our elected officials must be empowered to challenge the legal fraternity and restore to the Knesset the sole power to legislate laws.

Given the gravity of the situation, the disputes over Israel’s borders, its energy policies, its immigration policies, its economic policies and its military policies become secondary concerns. The key question that hangs in the balance today is whether the Knesset will restore its power as the repository of the people’s will in accordance with law or will it become a mere debating society with the actual power to determine Israel’s future devolved entirely to bureaucrats ruled by a handful of unelected lawyers and judges? Because if the latter happens, the people will lose all ability to determine the outcome of every other aspect of national life.

Every once in a while, over the past year or two, I found myself wondering whether I should throw my hat into the ring and enter politics. Could I be effective in advancing the goal of restoring the powers of the Knesset from inside the Knesset or am I better off staying where I am? Since this was a purely hypothetical question, I left it open.

This brings me to my decision this week to move to a new stop on my Zionist journey.

This week I decided to respond positively to an offer from Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked and Education Minister Naftali Bennett to join their new party, the New Right (Hayamin Hehadash), and run on their Knesset slate.

True, there is more than one party that reflects my views in the Knesset, at least officially. But in recent years, the political leaders who have done the most to translate my positions into action have been Shaked and Bennett.

They share my concern for Israel’s future as a democracy. They dare to insist that to restore and strengthen Israeli democracy, the current power balance between bureaucrats on the one hand and elected officials on the other must be turned on its head. Whether they are discussing the vast expansion of the power of military lawyers over field commanders in the IDF, the necessity of enforcing the laws of Israel over its Arab citizens with the same alacrity as it is enforced over its Jewish citizens, or rejecting the notion that the Supreme Court has the power to overturn Basic Laws, Bennett and Shaked have consistently communicated and advanced positions I view as critical for the future of the country.

No less importantly for me as a proud Jew who never understood what I see as a largely artificial distinction between religious and secular Jews, their new party doesn’t seek to serve just one type of Israeli. It seeks to represent the full spectrum of the Israeli society that I saw and fell in love with, in all its rich diversity, in that pivotal first visit in the summer of 1982.

I am convinced that restoring Israel’s democratic institutions is the most urgent task we face today. And while I would have been happy to continue advocating for legal reform from my position in the media, when Bennett and Shaked asked me to join them in their efforts to advance this goal from the Knesset, I said yes with little hesitation.

The Zionist journey I began in 1982 has taken me places I could never have dreamed of. It is my deepest hope and my intention that on my next stop, I will have the privilege of advancing the Zionist enterprise I fell in love with so many years ago.