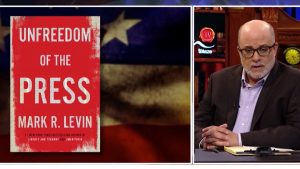

In his newest book, Unfreedom of the Press, Mark Levin demonstrates how the media in the United States have used their power not to provide the news but to shape political agendas to advance their progressive ideology.

Levin’s main contention in Unfreedom is that as presently constituted, the so-called mainstream media, which views itself as an activist media – that is, a partisan and ideological actor in public affairs in the United States rather than a neutral observer and recorder of events.

Given the progressive, activist media’s effective control over the public discourse in the U.S., today it acts not as the guarantor of freedom of expression, but as the most powerful bar to freedom of expression in America.

By determining what is “racist” and what is not racist, what is “politically correct” and what is unacceptable politically and culturally, the media do not serve as a vehicle for informing the public about the issues of the day and the state of the country and the world. Rather, they serve as indoctrination nodes, instructing the public what they can say and what they cannot say; what they can think, and what they cannot think; who can be accepted as legitimate and who must be ostracized and shamed as illegitimate.

One of the most significant chapters in Levin’s book appears at first glance to be out of place in his overall narrative. Most of the book is a discussion of the historical development of the media starting from the revolutionary period and continuing through the present day. He demonstrates how, beginning in the late 19th century, the media began presenting themselves not as partisans and champions of specific political factions and causes, but as objective observers whose function is to inform the public of current events. Their self-declared objectivity, however, was never entirely real. Indeed, it was deliberately dishonest. Because it was in this period that the media began to accept the terms of the progressive movement — which viewed the media, with its self-professed objectivity, as a central tool for advancing the movement’s radical agendas.

The non-objectivity of the media grew incrementally more predominant with each passing decade. And today, Levin shows, it makes little sense to talk about “bias” of the media because the bias is built into the system rather than related to one specific story or issue. The progressive mindset hasn’t been grafted onto an otherwise objective undertaking. It stands at the foundation of every major progressive news organization in America. The far left and antisemitic positions the New York Times stakes out, for instance, aren’t the function of one editor. They are reflections of the nature of the organization.

In the midst of his powerful narrative, tucked between a chapter on how the media use the 24-hour news cycle to create fake events, and another devoted to the media’s dehumanization of President Donald Trump, is a chapter that focuses on how, in the 1930s and 1940s, the New York Times deliberately hid the Nazi genocide of European Jewry from its readers.

In reading the chapter, the question arises: why is this event, (along with the Times’ whitewashing of Stalin’s decision to starve the Ukrainian peasantry in the 1930s, which the chapter also discusses) in this book? How is the Times’ refusal to expose the genocide of European Jewry in a significant way, as the atrocities unfolded, connected to the media’s current mission to advance progressive ideas, values, politicians, and political causes while dehumanizing President Trump and his family and advisors?

The answer is that in the Times‘ decision to block coverage of the genocide of European Jewry, we see how the ideological rigidity of media institutions can lead them to suppress vital information and endanger the lives of real human beings.

The roots of the Times’ malfeasance during the Holocaust are found in the Ochs-Sulzberger dynasty’s hostility to Judaism as it has been practiced and understood by Jews worldwide for thousands of years. Since the time of the biblical patriarchs and matriarchs, through to the present day, Jews have seen themselves as a nation, connected by ancestral ties of family and tribe, by a common legal code, and by attachment to their homeland, the land of Israel.

In the 19th century, an influential group of German and American Jews decided to reject this millennial identity. The Reform movement, founded in Germany and adopted by German Jewish immigrants to the United States in the mid-19th century, rejected the notion of Jewish peoplehood. Judaism, they insisted, is merely a faith. Jews have no national identity, and no specific uniqueness as a group. They deserve to live unmolested, but Jews in the United States are first and foremost Americans and as such, they should have no special attachment to Jews in other countries.

As Jerold Auerbach explained in his book Print to Fit: The New York Times, Zionism and Israel 1896-2016, the Ochs-Sultzberger family, which has controlled the Times since the family patriarch Adolf Ochs purchased it in 1896, has harshly insisted that the Reform Jewish perspective they hold be reflected in all of the Times’ coverage of Jewish issues generally and Israel in particular. The Reform position that Jews are not a nation placed it in direct conflict with Zionism. Although the movement formally accepted the legitimacy of Zionism in 1937, and again in 1997, the foundational creed of Reform Judaism places it at odds with Zionism, as it is at odds with traditional Judaism as a whole.

Auerbach’s work shows that for Ochs and his colleagues, it was impossible to accept the legitimacy of a differing view of Judaism. Ochs’s anti-Zionism was so extreme that in 1902, the Times published an article titled, “The Evil of Zionism.” It argued that Zionism and antisemitism were “twin enemies of the Jews, and the former is potentially more dangerous.”

After Ochs’s death in 1935, the gavel of leadership passed to his son-in-law, Arthur Hays Sulzberger. And Sulzberger continued Ochs’s legacy, at Jewry’s darkest hour. Sulzberger viewed any mention of the fact that the Nazis were targeting Jews specifically for persecution and mass murder as tantamount to accepting that Jews are a people. And so Sulzberger ordered his correspondents in Europe to hide the fact that the Nazis were specifically targeting European Jewry for annihilation.

In Unfreedom, Levin summarizes Laurel Leff’s findings in her book, Buried in the Times: The Holocaust and America’s Most Important Newspaper. Leff demonstrated that Sulzberger’s rejection of Jewish peoplehood, and his desire to avoid having the Timeslabelled a Jewish paper due to his Jewish faith, is what stood behind the Times’ failure to cover the Holocaust in a meaningful way. And it wasn’t that Sulzberger was unaware of what was really going on. While he hid the story of Hitler’s war to annihilate European Jewry from his readers, he helped rescue his Jewish relatives from Germany.

Sulzberger’s stunning decision in the face of the genocide of European Jewry ensured that the Roosevelt administration was never significantly pressured to take any meaningful steps to rescue European Jewry.

Auerbach shows that the same counter-historical, anti-Jewish radical ideology — that Jews are not a people — has continued to shape the Times’ coverage of Israel and of Jewish affairs more generally in the eight decades that have passed since the end of the Second World War.

This brings us to the logic of Levin’s decision to devote a chapter of his general analysis of the state of the American media to a chapter on the Times’ refusal to report on the destruction of European Jewry in the Holocaust.

The late historian of antisemitism Robert Wistrich observed once, “What starts with the Jews, never ends with the Jews.” The Times’ hostility to Jewish nationhood now extends to a hostility towards American nationhood. If in 1902, the Times demonized Zionists as antisemites, today they demonize Americans who want to preserve the national identity of America — by, among other things, controlling the U.S. border with Mexico — as Nazis and fascists and racists.

Levin’s book is a wake up call to all Americans. Information and speech suppression by ideologically motivated media is devastating to societies and to individuals. Prioritizing ideologies over human lives costs human lives.